1) Making a difference in writing achievement

What makes a difference in writing achievement when working with Year 5-8 priority students: A national research project.

Funded as a Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI), our goal was to work collaboratively 2016-2017 with school leaders and teachers from five decile 2-8 schools at inquiring into what making a difference in writing for priority learners (particularly boys, Maori students, Pasifika students) looks like in typical and authentic Year 5-8 classrooms. We worked with Balmoral School (Auckland), Clayton Park School (Auckland), Fergusson Intermediate (Wellington), Marshall Laing School (Auckland) and Mt Cook School (Wellington).

I co-led the project (with Professor Judy Parr) but I took responsibility for leading the school-based aspects of the project; namely, working directly with schools and teachers on instructional actions that make a difference. I will describe one set of findings (those for 2017) only.

We worked directly with 5 literacy leaders, 15 teachers who had volunteered to be part of the project and 367 students from diverse ethnic backgrounds during the year.

Initial student achievement data (using e-asTTle writing) indicated significant under-achievement, with more students in the ‘well below’ achievement band than in any other band. Teachers used this data to select 3 touchstone or target students whose progress they would inquire into closely in relation to their use of selected instructional actions. Teachers were required to keep reflection journals (that we had designed) for each touchstone student – progress the student was making and what the teacher had done to generate progress. Student voice also needed to be included in the journals.

What we did

During the year:

- I ran workshops on the key dimensions and instructional strategies that research literature (including my own) indicated as critical in affecting stronger engagement and greater progress by students;

- I modelled how some of these dimensions and strategies could be operationalised in classrooms;

- I observed each teacher’s practice three times and rated their practice for each of the key dimensions and strategies using a rating tool that we had designed from the literature; we required teachers to self-rate their practice as well so that we could hold informed discussions about practice;

- We required teachers to gather T2 e-asTTle writing data to measure T1-T2 differences; and

- We gathered information from each teacher (from interviews and analysis of comments in reflection journals) on what they believed had made a difference for their students, particularly their touchstone students.

Some results

We collected, analysed and synthesised three sets of data:

Student achievement. There was considerable positive movement between T1 and T2 with 9.9% movement for ‘all students’ from the below/well below to the at/above achievement bands. At T2, there were more students in the above band (40.8%) than in any other band. Boys (n=171) made significant progress with the proportion in the above band increasing from 20.5% to 33.7%, and the proportion in the well below band decreasing from 35.2% to 14.4%. Maori students (n=73) also made significant progress with the proportion in the above band increasing from 18.4% to 44.8%, and the proportion in the well below band decreasing from 44.7% to 8.6%.

Arguably, the most positive finding was the progress made by students who began the year at an achievement level significantly below expectations (at the beginning of level 3 or below) (n=123). On average, 56.4% made accelerated progress (3 sub-levels or more) and 31.6% made expected progress (1-2 sub-levels). The data clearly showed a far greater rate of progress than most of these students had previously achieved.

Teacher proficiency. From the series of in-depth observations of writing lessons, the average proficiency score for all teachers (as rated by both observers and teachers themselves) increased by 9.8% from T1 to T2. By the end of 2017, the mean for ‘all dimensions’ was 3.07 (out of a maximum of 4.0) with scores for direct instruction (3.25), knowledge of writers (3.14), learning goals and tasks (3.11) and differentiation (3.11) exceeding this. These findings suggest that teacher proficiency was greater around these dimensions (direct instruction; learning goals and tasks; knowledge of the writer; differentiation) than it was for others.

Practices effective with touchstone students. Teachers believed that actions related mainly to the four dimensions that rated most highly for teacher proficiency made the difference for advancing the engagement and progress of touchstone students:

- Knowledge of students (getting to know the students really well; knowing individual needs and keeping track of them; using humour/fun as a relationship tool);

- Learning goals/learning tasks (encouraging student initiation and contribution, especially in topic selection);

- Direct instruction (using active modelling and receptive modelling; breaking tasks into more manageable components; making links between reading and writing);

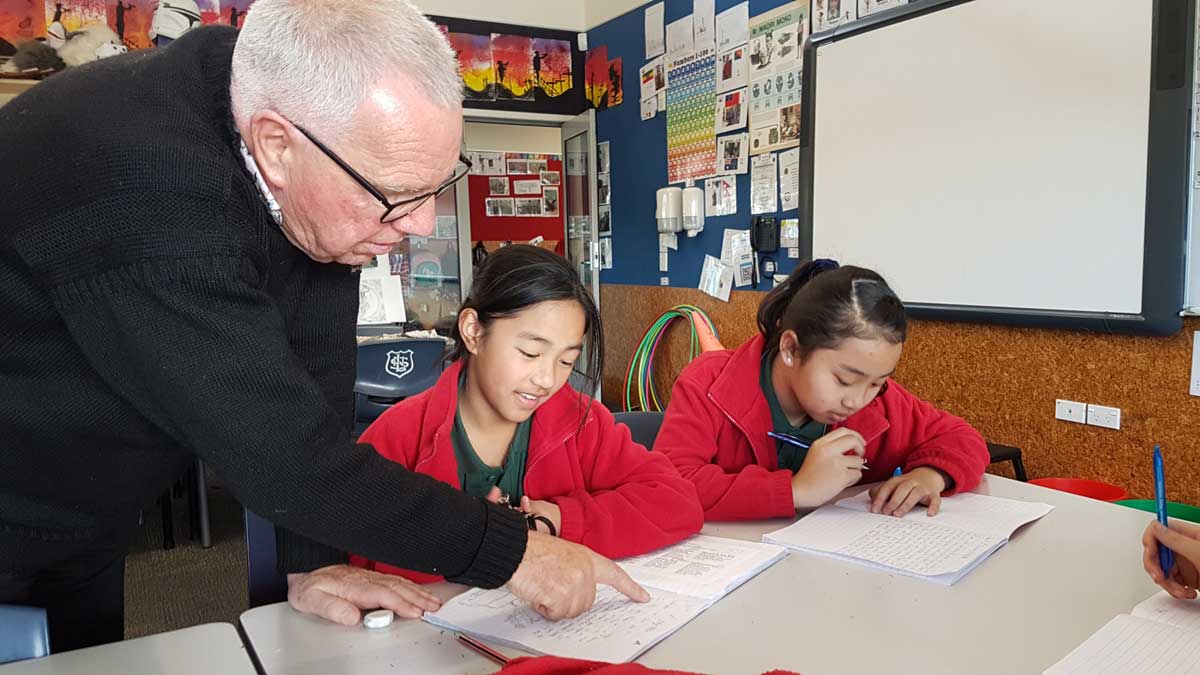

- Differentiation (touching base often with touchstone students; working with touchstone students in small groups based on needs not ability; using a tuakana-teina approach; using different scaffolds according to student needs).

In addition, actions related to Self-regulation appear, from teacher reports, to be very important (helping students to manage their time better; seeking resources to support independence/self-monitoring; encouraging self and peer assessment).

A full set of results can be accessed by clicking here and if you would like further information, please feel free to contact me.

2) Enhancing teacher knowledge and instructional practices

Raising student learning and achievement levels in writing through enhanced teacher knowledge and instructional practices: a school-wide project

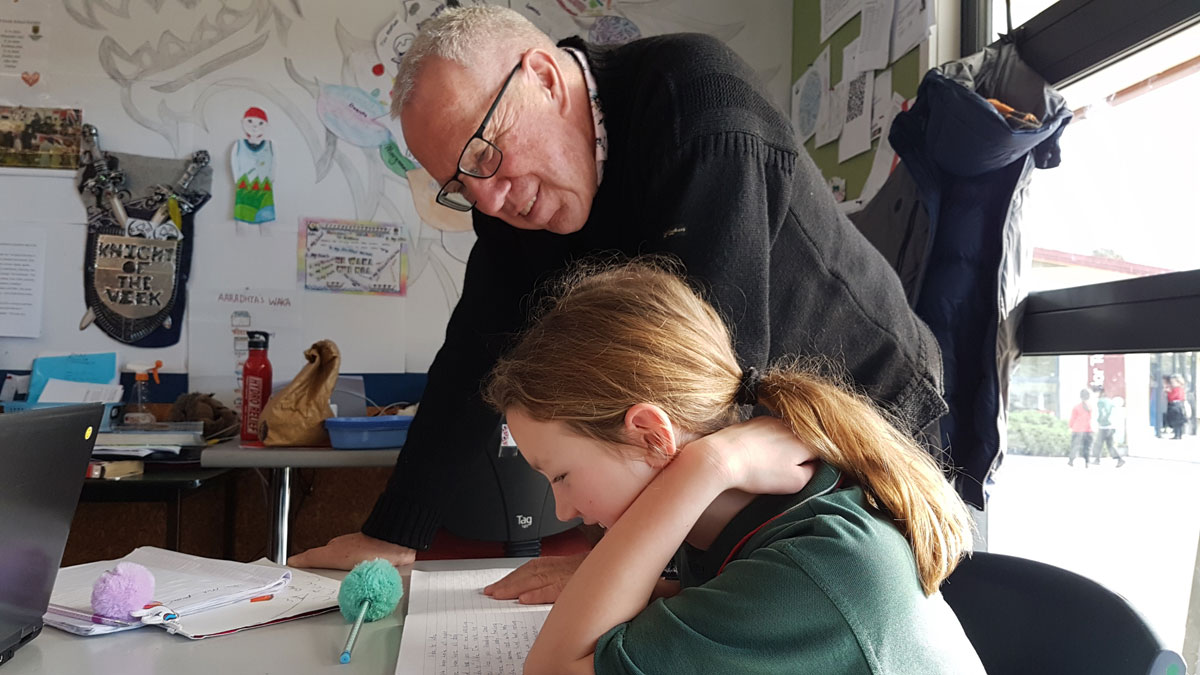

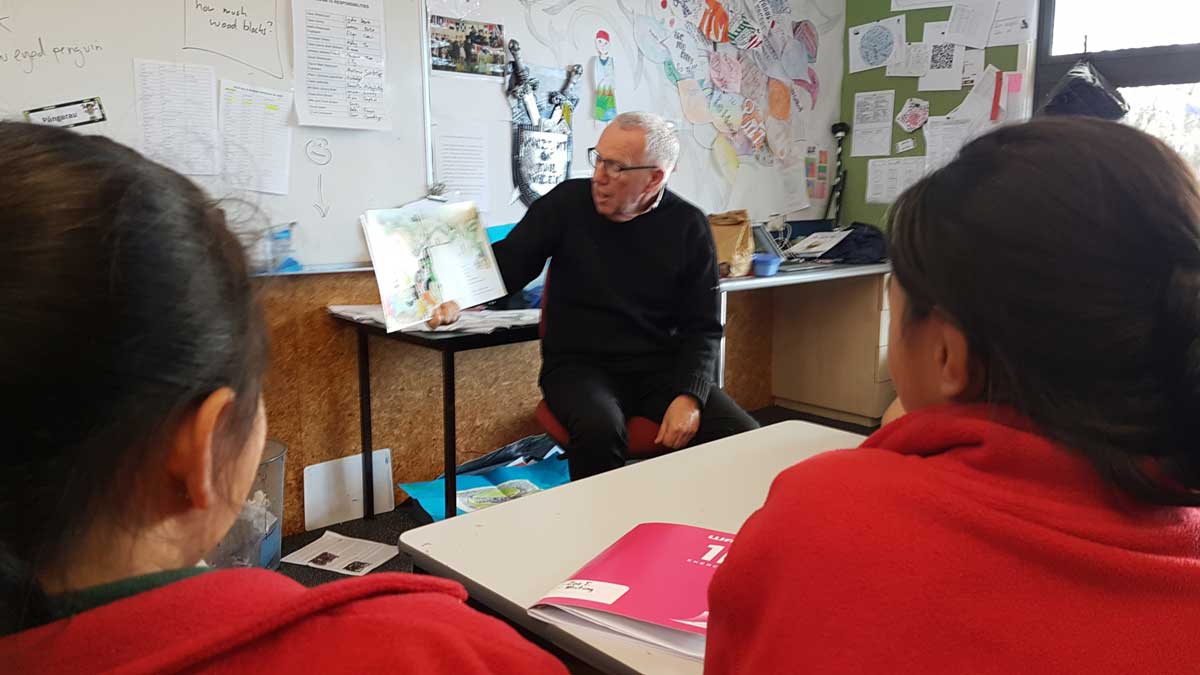

This was similar to the national research project but more in-depth at the classroom level. It was begun in 2017 and is continuing. It is being undertaken with a full primary school (Templeton: roll, 336; decile 8) in a semi-rural setting just out of Christchurch. Achievement levels in writing had been reasonably good – by the end of 2016, 71% of students had achieved (according to OTJs made) at or above national expectations – but the principal felt that student engagement and achievement levels could be lifted even further. As in many schools, there was significant underachievement by boys, especially in senior classes.

What we did

During the year I:

- Led workshops on working effectively with struggling/reluctant writers and with a particular focus on boys; holding teacher-student conversations about writing; making reading-writing connections, and promoting literacy across the curriculum. This was in addition to a Teacher Only Day on what constitutes an effective writing programme (content and organisation).

- Modelled effective writing instruction in diverse classrooms at the whole class level. Teachers were encouraged to observe and reflect on how to engage students in a topic/task, set students up for a writing task, and differentiate instruction across the class.

- Modelled how to implement small group workshops through analysis of students’ writing/data. I worked with teams of teachers at analyzing a sample of writing from each of a group of similarly-levelled students, looking for strengths/needs/goals for each student and for the group, and then working with students (as a small group) at identified needs.

- Held practice analysis conversations (following close observations of small group writing lessons) with all teachers over the year. Each teacher also received detailed written feedback on their practice.

- Led a parent/community evening on what students do as they write, how students learn to be good writers and what parents/whanau can do to support their children as they become writers.

I also established (in collaboration with the literacy leadership team) a teacher inquiry process whereby teachers inquired into the impact of their instructional practices on 2-3 under-achieving or target students’ progress.

Toward the end of 2017, I also established (in collaboration with the literacy leadership team) a process whereby leaders and teachers could determine the progress made by their students (including their target students) over the year, based on their OTJ judgements, as well as their own progress as developing teachers of writing. This enabled them to set targets, goals and directions for 2018, both for their students (as individuals and cohorts) and for themselves.

A key feature of this project is the close involvement of both the principal and literacy leadership team in all aspects of it. As examples, the principal participates in all learning sessions, all observations and all practice analysis discussions, and the literacy leadership team is released en masse for the duration of each of my visits. They participate in all learning sessions, all observations and all practice analysis discussions as appropriate to their level of the school. They also undertook 33 lesson observations between my visits.

Some results:

Student achievement. Overall progress was reasonably good with 75.7% of ‘all students’ achieving at or above national expectations compared with 71% at the end of 2016. But it was variable for year level cohorts with a range of 44%. However, 6 out of 7 year level cohorts made progress (by an average of 6.5%) from their 2016 achievement levels.

Both boys and girls achieved above the national results for their cohort – boys by 2.6% and girls by 7.6%. But there was still a 21% achievement gap between boys and girls across the school, particularly in the senior classes.

NZE (n=246) and Maori (n=71) students achieved at a similar level with 75% of NZE students achieving at or above national expectations by the end of the year compared with 76% of Maori students.

Teacher practice. Our observations suggested that teachers need to continue working on:

- using learning goals as effectively as possible during lessons (letting the learning goal (and genre) emerge from the task: “So what do I have to be good at as a writer to do this task well?” and referring back to the learning goal/s during and at the end of modelling sessions: are we achieving what we set out to achieve?);

- demonstrating as effectively as possible (continuing to refine aspects of active modelling that emerge, particularly ensuring that all students are engaged in the modelling process); and

- refining workshops as effectively as possible (continuing to be clear with students about the skill being taught and try not to go beyond that, and putting the writer at the forefront of the workshop but in a positive/ non-threatening way).

Next Steps

The facilitator, principal and literacy leadership team shared all of the above data with teachers at the beginning of 2018 and everyone – collectively – decided on goals, targets and directions for 2018 and 2019. It was agreed that teachers would identify every student at the beginning of each year who is in ‘below’ + ‘well below’ bands for writing (n=94) and set an achievement target and goal for each student and think about the teaching approaches/actions that are needed in order to help the students reach their targets/goals.

It was also agreed that teachers would iteratively ask questions of themselves about ‘time given to writing’, ‘topic and task selection’, ‘programme organisation’, ‘making links between writing, oral language and reading’, and ‘their own knowledge of the encoding and processing strategies that their students need to develop’. They also agreed to discuss and analyse the progress of their under-achieving students regularly at the team level.

We are currently – during 2018 and 2019 – working on addressing these goals, targets and directions.

3) Helping students with intellectual disabilities become better writers

Helping students with intellectual disabilities become better writers: An off-shore inquiry into writing instruction

This is a brief summary of the first episode of a four year off-shore project that I am currently undertaking with a group (n=8) of Swedish students with intellectual disabilities (ID) to see whether the findings that international researchers (including myself) have made about the effective teaching of writing for typically performing students apply to working with students with ID.

The students (aged 16-20) comprise an English language class at a Stockholm special needs school; their teacher felt that they had sufficient English to cope with the challenges of such a project. They have had limited experience, however, in writing extended texts, particularly in English.

What I did

I planned a series of 9 writing lessons (around 3 personal or creative narrative topics) that I delivered over a 10- week period. Each lesson lasted 45-60 minutes. As I planned, I ensured that the instructional strategies I proposed to use aligned with the strategies that international researchers say ‘work best’. This resulted in my attempting to:

- engage students through a purposefully selected open topic;

- develop possible content related to the topic;

- establish a clear writing task aligned to the topic;

- develop criteria for success with students or remind them of criteria if already developed (‘What will we have to be good at as writers to do this task well?’);

- demonstrate how to get ready for writing;

- differentiate the instructional support given to students by inviting them to either remain with me or work independently;

- model expected outputs to students, especially those requesting or requiring additional support;

- hold rich conversations with students about their writing; and

- encourage students to share and celebrate their writing achievement.

I shared my planning with my Swedish colleagues (including the teacher) before each lesson and they confirmed that it represented a different pedagogical approach to what the students normally experienced. Typical writing lessons for these students were focused on skill-building (especially grammar and spelling) rather than a topic.

In addition, differentiation was rarely planned for. Our question was: Would my topic-driven approach which was under-pinned rather than driven by skill-building make a difference?

Some results

It appeared to make a difference. Using a quantitative measuring tool that we had developed, we noted considerable progress between the beginning of the 10 weeks (T1) and the end (T2):

- All students had increased their writing productivity (from a mean of 87 to 181 words; and from a mean of 6 to 17 sentences).

- All students had increased their sentence lengths (from a mean of 9.5 to 12.1 words) as well as the complexity of their sentences and texts (from a mean of 8.7 to 21.5 ideas per text; and from a mean of 25% to 46.5% compound or complex sentences per text).

- Most students had also decreased the proportion of grammatically irregular sentences in a text (from a mean of 56.9% to 29.5%).

There was, however, just a small increase in vocabulary richness (from 17.9% to 19.8% of words being above the 1000 most commonly used words) and only a small decrease in the proportion of spelling and punctuation errors per text (from a mean of 29% to 25.2%).

As an initial finding, this seems to confirm a conclusion I reached in my doctoral research: ‘what is good for all is particularly good for students facing greater challenges than others’. In this case, the ‘greater challenges’ were disability, language and experience-related.

This work is on-going, with work needing to be done with greater numbers of students, replicated to students writing in their first language, and opened up to take account of other possible reasons for acceleration, e.g. taking account of greater teacher knowledge or stronger teacher aptitudes for literacy teaching and learning.