AUGUST 2023 – JANUARY 2024

The past six months have been very hectic for me – finishing off the school year and getting my own book ready for publication – but I have managed to do a considerable amount of reading and viewing.

READING

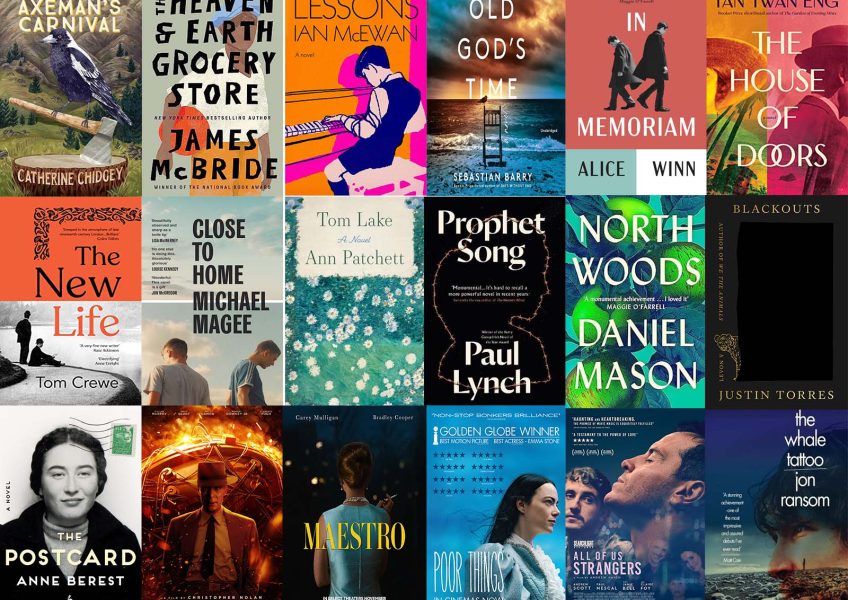

I have read 18 works of fiction over the past six months and (as usual) they have been a mixture of ‘the very best of the year’ and books that didn’t particularly engage me. In order of what I’ve read:

The Fraud by Zadie Smith. I have loved reading Zadie Smith ever since the publication of White Teeth in 2003. And, in theory, I believed that I would love this book as well – almost a social history of London and its surroundings in the 19th century; moving between London and Jamaica (the land of Smith’s ancestry); based on real people and events (including a courtroom trial that fascinated the working class in the 1870s); contextualised within a world of writers and literature (including Dickens and Thackeray). But, in reality, it didn’t engage me as much as I had anticipated. Told in small fragments, and across time spans, I never felt as involved as I thought I would. And the third of the novel that is set directly in Jamaica seemed almost like an imposition on the main thrust of the narrative to me. Sure, the novel has something to say – about the fractured nature of reality – but this was not enough to satisfy me. Even the suggestion (made by a New York Times reviewer) that the fraudulent character at the centre of the courtroom trial and his ridiculous lawyers were pastiches of Trump and Guiliani did not do it for me. I still look forward to Smith’s next novel though.

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch. This extraordinary novel had me gasping from time to time and I couldn’t put it down. Parts of it jolted me more than I could imagine. Could this really be happening? Yes, it could as I recalled images of political refugees fleeing from Syria, Ukraine and Nazi Germany in the direst of circumstances. The natural off-spring of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and George Orwell’s 1984, this Dublin-based tale is of a working mum’s increasingly desperate and very moving attempts to hold her family (including a newborn and her father with dementia) together as a totalitarian regime takes over Ireland. The beautiful but sometimes bruising prose swept me along and I was not as disturbed by the lack of paragraphing as I thought I’d be. I soon recognised that this helped to generate a sense of tension and claustrophobia in this brilliant dystopian novel. Everyone, especially politicians, should read it. Last year, I discovered the wonderful Percy Everitt through the Booker Prize longlist; this year I have discovered the equally wonderful Paul Lynch. I was neither surprised nor disappointed that Prophet Song won the prize for 2023.

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray. I loved this lengthy family saga that everyone is talking about. Set in a small town just outside of Dublin and just after the 2008 financial crisis, it focuses on a family of four – father (Dickie), mother (Imelda), daughter (Cass), and son (PJ) – and depicts their lives falling apart as they think aloud their current predicaments and recall their past lives. Each character has their own set of secrets which they skilfully narrate apart from each other. It sounds heavy but it ultimately isn’t. At times, in fact, it is laugh-out-loud and reminded me of the best of Jonathon Coe’s state-of-nation tragicomedies. To me, it was a page-turner as I was desperate to find out what happened to all the main characters, and I think I agreed with the Guardian reviewer who described it as “a tragicomic triumph” and declared that “you won’t read a sadder, truer, funnier novel this year”.

The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store by James McBride. This absolute page-turning murder-mystery is yet another contender for the Great American Novel. Set in Pennsylvania in the 1920s and 30s, it is foremostly about community – an impoverished mixture of Jewish, Black and immigrant folk who do not always get on but support each other beautifully to rescue a disabled black child from the clutches of white supremacy. McBride not only propels a great narrative with force and verve but he can also bring alive characters who seem real to the touch. Every detail counts in this book. But it is also an examination of the racial, political, religious, economic and social divides of the working class community portrayed in the novel, thus putting another bullet into the great American Dream. But, underneath all of this, warmth, laughter, love and just a little bit of hope still prevail. I didn’t want this novel to end, and was not surprised that it was placed in the New York Times’ best five list for 2023. It would be on my list as well.

Chain-Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah. I admired this novel more than I liked it. Yes, it has something important to say (about the horrors of extreme incarceration); yes, it is peopled by fascinating characters (particularly the two Xena-warrior princess leads); yes, it is fast and told with exhilaration. It is, in fact, a dystopian novel – an alternative for prisoners waiting on death row is to participate in televised gladiator fights to the death for the entertainment of paying subscribers – and it is even more horrifying in that it is not set in the future, but in today’s America, as evidenced by the footnotes that accompany it. But its stage is too vast and too muddled to ultimately engage me, and by the end I had little interest in who lived and who died. I didn’t really care for any of the characters, even those who were fighting the injustices of the situation.

If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery. This powerful and sometimes explosive collection of heavily linked short stories – set largely in or around Miami and featuring a family of Jamaican-Americans – is all about survival: survival against racism, poverty, classicism and financial chaos. How can a father treat his sons like Topper does? How can two brothers treat each other like Delano and Trelawny do? The hurricanes that beset Miami throughout the novel act as metaphors for the hurricanes that envelop these beautifully drawn characters’ lives. But it is also a book about identity as Trelawny tries to work out his place in society. This book engaged and intrigued me in its sad but sometimes humorous depiction of the American under-belly. The American Dream gone wrong again?

This Other Eden by Paul Harding. Despite its beautifully created poetic sentences, this short novel did not engage me as I expected it to. I anticipated that its subject matter – a re-imagining of an ugly episode in America’s racist past – would totally engage me but it didn’t. Its story of a small multicultural community being cleansed from a small island off Maine in 1912 did not move me as I thought it would, partly because its lyrical language kept me at a distance from the story-telling. It is, I acknowledge, ultimately a story about love – love for one’s family, love for one’s ancestry, love for one’s environment – but the love did not pour into me. I recognised its beauty but was not captured by its story-telling.

Tom Lake by Ann Patchett. I loved reading this book and felt sad when I had finished it, just as I had felt sad when I finished reading Patchett’s previous novel The Dutch House. Yes, it’s a bit sentimental; yes, it’s a bit like a fairy tale; but it worked beautifully for me. It is essentially about a strong but gentle central character putting her life in order and realising how lucky and happy she is, as she explains her connections to a famous Hollywood actor to her three grown-up daughters during a pandemic lock-down on the family cherry farm. But two writers hang over the novel – Thornton Wilder and his play Our Town (which is the catalyst for many of the main events in the novel) and Anton Chekhov and his plays The Cherry Orchard (the obvious setting of the story-telling) and The Three Sisters who are together for maybe a final time. In fact, a Chekhovian mood of wistfulness linked with ongoing anxiety pervades this novel. As a person who loves the plays of Chekhov, and indeed the theatre, I found the novel deeply satisfying.

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo. This gentle novel, told in the first-person by eleven-year-old Gopi whose mother has just died, focuses on the grief that Gopi experiences (much of it unspoken) as she attempts to continue her life with her loving but taciturn father, her two teenage sisters and several other family members and friends. But her (and her father’s) obsession with squash starts to take over her life and the sounds of the sharp but hollow ball hitting the four walls of the court become a metaphor for the girl’s emotions. Others have described this debut novel as lyrical and beautiful – I can see where they’re coming from – but neither the main character nor the sport engaged me as I was hoping.

Northern Wood by Daniel Mason. I really liked this book. Had I held a greater/stronger interest in ecology, I might’ve liked it even more. But it is a fascinating novel and unlike anything I have read before. It is basically the story of a house in West Massachusetts and its surrounding forest/bush, told chronologically from the eighteenth century to the near present or even the near future. Each episode brings a new character or set of characters – often misfits and almost always quirky – to the house and its land, and they invariably leave behind mysteries for others to solve. But it is not just a story of the characters – it is a story of the house itself and the surrounding vegetation and live-stock. All in all, it is a story of the inevitable social, political, economic and of course ecological changes that are looming down on the world. It is clever – some episodes are straight recounts or narratives; some are newspaper reports; some are letters or speeches; some are ballads; some are visual relics or reminders. To me, it was a very satisfying read – it does not surprise me that it has made the New York Times top five novels of 2023 – but it would have been an even more satisfying read for me if I had more knowledge or a stronger interest in the ecology that contextualises it. Those who hold this knowledge or interest will love this beautifully told story.

A Spell of Good Things by Ayobami Adebayo. I really liked this novel and was incredibly moved by it, especially its final explosive quarter. Contextualised heavily within contemporary Nigeria, it places two divergent characters and their families alongside each other – the wealthy Wuraloa who has trained to be a junior doctor and has high professional ambitions, and the poverty-stricken Eniola who will do anything to move beyond his poverty-stricken life – but also brings them together as social and political tensions overtake them and their families. But its themes are bigger than Nigeria – the economic poverty, political ruthlessness and gender abuse portrayed here could be happening anywhere. The novel – Adebayo’s second – was longlisted for the Booker Prize. I would’ve been very happy if this page-turner of a novel was placed on the short-list. Unfortunately, it wasn’t.

Study For Obedience by Sarah Bernstein. This compact novel appears to be a study of survival. An unnamed female narrator moves to an unnamed foreign land to tend to her brother. Almost bullied by her brother, spurned by the local townspeople and superstitiously blamed for misfortunes that beset the town, the narrator survives through obedience. She accepts her lot – sees herself as a victim – and tries to quietly get on with life as she has always done. But sitting behind her story are signals of the Holocaust. She is probably Jewish – is this why she is hated so much and what do the references to the ‘pits’ mean? A somewhat enigmatic novel and it will not be for everyone. There were times when I wanted to give up – what was actually happening? – but there was always something behind the enigma that made me want to read on.

Close to Home by Michael Magee. I really liked this debut novel by Michael Magee and predict that he will become a major writer. Set across the working class and student districts of Belfast fifteen years after the Troubles, it is about a young man trying to ‘find himself’ – having graduated with a degree in English Literature from Liverpool, he has returned to Belfast but recognises that he doesn’t fit into his working class background as comfortably as he once did, nor does he feel totally comfortable in the middle class/artistic milieu (he aspires to be a writer) that he wants to live within. It is a study of contemporary masculinity as shaped by place and class. Yes, it contains copious amounts of drinking and drug-taking as well as occasional violence – some people have described it as the Shuggie Bain of Belfast – but there are also welcome signs of hope and optimism toward the end. Some of the dialogue is colloquially Irish and difficult to understand, but the narrative thrust is powerful and direct. I highly recommend it.

The Wren, the Wren by Ann Enright. The is a sad but also life-affirming novel. It centres around three strongly Irish voices – Nell, a young woman trying to break a familial bond as she travels the world (including a stint in Auckland); Carmel, her mother, who is trying to make sense of her broken family background; Phil, Carmel’s father but also a famous Irish poet who deserts the family to live a literary life in America. There is much cruelty in the novel – sometimes planned but more often incidental – but also warmth, mainly implied by the birdsong that pervades it. Much of the birdsong is portrayed by the lyrical and descriptive poetry that Phil pens. Enright’s huge skill is in being able to manage ever-so-cleverly the many narrative thrusts and turns of the novel in a way that keeps these diverse characters’ lives propelling forward, individually and collectively. We want them to find peace and contentment.

Blackouts by Justin Torres. Justin Torres’ new novel is like an extended dream and conversation between an older dying Puerto Rican gay man (real or not real?) and a young decidedly alive Puerto Rican gay man (Torres himself?). The novel is dream-like because it drifts between stories and reminiscences, photos and artifacts. Some are real, based on the work of the real-life sociologist Jan Gay, and some are truly imaginary and imaginative. But, overall, it is about two generations of gay men determined to piece together (from actual and metaphorical blackouts) their representative queer history. By the end, the younger man has promised to keep writing it. I read the novel primarily because it won the 2023 National Book Award in America, but I was pleased I did. The characters and the stories swept me along, and although ‘lyrical’ is not normally my preferred genre, the book sang to me at a far deeper level than I had anticipated. I suspect this novel will become a classic of gay literature.

The Postcard by Anne Berest. This is a very powerful book translated from the French by Tina Kover. I am loath to refer to it as a novel because it is not only based on real events but includes characters that we can actually research – Francis Picabia, the avant garde artist; Manuel Ranby, a leading actor in Jean Renoir’s cinema company. But Berset, who is partly telling her own story in this incredible book, brings both the events and characters to life so vividly, you need to think of it as a novel with a ‘real’ background. Maybe autofiction? It begins with the arrival in the post of an anonymous postcard with nothing but four names on it – the names of Berest’s great-great grandparents, great aunt and great uncle who were all murdered at Auschwitz. The novel then becomes an investigation – who were her murdered relations and how were they actually murdered, and who sent the postcard and why. We do not learn the answer to this final question until the last page which contributes to the un-put-down-ableness of this extraordinary book. Every page is revelatory. But it is also about Berest learning what ‘being Jewish’ is all about. It works on so many different levels. Not since reading Daniel Mendelson’s The Lost have I been so affected by the Holocaust experience through my reading.

Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck. Essentially, this novel is a love story – a love story between a 19-year old single female journalist and a 53-year old male writer married with a teenage son. It is set very specifically in East Berlin just prior to the fall of the Wall, and part of its interest for me is its detailed depiction of East Berlin in the 1980s. But it is a love story that is doomed from the start. Within the first few pages, we learn that he male (Hans) has died and the female (Katharina) is left with his writings. But has she moved on? I ask this because pain and pleasure permeate this love affair – as they do the book – in equal amounts. But sitting behind (and indeed within) the love affair is the East German political context which involves both pain and pleasure. As the affair begins to disintegrate, so do East German politics. In fact, the most engaging aspect of the book to me was the impact of the fall of the Berlin Wall on East German citizens. Some, including the male protagonist, do not survive it. The rest of the world celebrated the fall of the Wall; many East Berliners were not ready for the West to be thrust upon them. This, ultimately, interested me more than the love story did. I, unlike many other reviewers, did not get emotionally engaged in the affair. But, on the other hand, I admired the wonderful writing of Jenny Erpenbeck (as translated from German by Michael Hofmann) and can understand why many consider her to be a future Nobel Laureate.

The Whale Tattoo by Jon Ransom. The is a tough but (to me) un-put-down-able novel. Joe, a gay lad, has returned to his Norwich sea-side village (after two years in hiding) to try and make sense of his life. But this is much harder than he imagines. We soon learn that he is trying to make sense of the love of his life (Fysh), his supportive sister Birdee, his nasty and homophobic father and a range of other very real characters. It is full of secrets and lies which slowly unravel. Or do they? Ransom enables the tension to be built up beautifully. Death is everywhere in this book – all predicted by the dead titular whale that Joe has seen – but glimmers of hope shine through. As tough as it sounds, this book is not a downer – it is ultimately the tale of a young queer lad trying to make something of his life in a tough world.

MY NOVELS OF 2023I have read 36 novels over the past twelve months and two stood out for me as my ‘best of 2023’. Like the Booker Prize judges, I place Prophet Song (by Paul Lynch) and The Bee Sting (by Paul Murray) at the top of my list. Lynch and Murray are both Irish writers but that’s where the similarity between the two novels ends. Prophet Song is as horrifying as The Bee Sting is exhilarating but both had me mesmerised. Both, I predict, will become classics of their type over time. A very close runner-up for me is the very powerful French novel The Postcard by Anne Berest. My other highly recommended novels from 2023 are:

STOP PRESS: Just learnt today that The Bee Sting has won the best novel award at the inaugural Nero book awards, and Close to Home has won the award for the best debut novel. This is great.

|

VIEWING

My movie-going over the past six months has been divided into two groups – movies I watched as part of the 2023 International Film Festival and movies I watched toward the end of the year as potential winners of the 2023-2024 award season.

From the Film Festival:

- Kidnapped. This Italian movie was probably the best I saw at the 2023 Film Festival. Epic in scope and gorgeous to look at, it tells the true story of a Jewish baby being kidnapped by the Catholic Church and being brought up by them, with direct links to the Pope. It fascinated and totally engaged me.

- Anatomy of a Fall. I am pleased to see that this Swiss/German/French movie is nominated for several Oscars. It deserves to be. Investigating whether the lead character killed or did not kill her partner, it follows her court case in a way that I have never seen before. It had me thinking and guessing until the end.

- La Chimera. Another fascinating Italian movie which reminded me of early Fellini movies, especially La Strada. A group of tomb robbers (searching for ancient antiquities to be sold on the black market) behave joyfully like a circus troupe. Highly entertaining.

- L’Immensita. Another great Italian movie. This is a melodrama set in the 1970s and starring Penelope Cruz. She is in a difficult and abusive marriage and does her best to keep her family (including her transitioning daughter) together. Very powerful.

- May December. This really entertaining American movie (starring Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore) tells the fascinating story of a marriage that started as a ‘crime’ – an older female teacher seduces a very young (13) male student but only because they love each other and this leads to a very successful long-term marriage. As a film crew attempt to explore the unconventional relationship, its details unravel in a way that disturbs everyone.

- Of an Age. This Australian movie tells the coming out’ story of a 17-year old’s romance with a friend’s older brother. It is always fascinating to see other people’s coming-out stories, especially one so truthfully told as this.

I would recommend all of the above films if they were to return on general release, as Anatomy of a Fall already has and as May December is about to.

From the upcoming award season:

- Oppenheimer. To me, this is an outstanding movie and deserves all the awards it gets. Its story is fascinating (events leading to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and the aftermath of this), its exploration of the ethics around atomic bombing is deep and intelligent, its performances are outstanding (particularly Cillian Murphy and Robert Downie Jnr) and its technical prowess is amazing.

- Maestro. I really like this movie about the great American composer Leonard Bernstein, probably best known for the music of West Side Story. Both Bradley Cooper and Carey Mulligan (as Mr and Mrs…) are fabulous, with Mulligan giving one of ‘the’ female performances of the year. But for those expecting a straight biopic of the composer, they will be disappointed. It is more like impressions of his life, but they are very powerful.

- Napoleon. I was really disappointed with this (very long) movie. The battle scenes were spectacular but I felt that I learnt very little more about Napoleon as a person than I knew before watching it. Despite its technical greatness, to me the movie lacked depth.

- The Holdovers. I was also slightly disappointed with this movie, though not nearly as much as I was with Napoleon. The story (about a disillusioned teacher and his relationships with his students) is engaging, the performances are very good, and the design is great, especially the outdoor scenes. But, to me, this is little more than a ‘feel good’ movie and I was hoping for more depth.

- Poor Things. This is an extraordinary in-your-face movie and I loved it. it tells of a young woman (superbly played by Emma Stone) being brought back from the dead and having to learn how to ‘live’ again. Some of the episodes – especially when she travels (with the wonderful Mark Ruffalo) – are almost breath taking. Ever since seeing The Lobster at a film festival several years ago, I have hung out for director Yorgos Lanthimos’ movies.

- Saltburn. This is another quirky plus, in-your-face movie. A (seemingly) working class boy (played by the great Barry Keoghan) moves into the upper classes and starts to ‘take over’. It’s a combination of Brideshead Revisited and The Talented Mr Ripley. Some of the scenes are hysterical, especially the graveyard scene and the final dance. What exactly is going on??

- All of Us Strangers. This movie is extraordinary. Again, you ask yourself what exactly is happening but in a very different way to Saltburn. It is about loneliness and memory with Andrew Scott giving, to me, the male performance of the year as a young-ish gay writer shutting the world out of his life. But to what end? This film moved me incredibly.

Of the many streamed series I have watched over the past six months, the continuation of two of my favourites (Slow Horses on Disney and Fargo on Neon) have stood out for me. Both totally engaging and so well made. Both full of tension. And I am midway through watching Boy Swallows Universe (from the excellent novel by Trent Dalton) on Netflix at the moment. Loving it, despite its predilection for graphic violence.

What do you think? Share your thoughts...