Part of this time was spend in Europe; part was spent back in New Zealand. Because life in both locations has been absolutely hectic, I have not been able to read or view as much as I normally would in a three-month period. Hence 9 novels only, and a small amount of theatre going. Mind you, quantity doesn’t align with quality. Despite the low number of books read and plays watched, some of what I have read and watched has been amongst the best of the year so far.

BOOKS

The Axeman’s Carnival by Catherine Chidgey. Having just read and loved Eleanor Catton’s Birnam Wood, it was so interesting to move on to reading (and loving) another novel set in heartland rural New Zealand – Catherine Chidgey’s The Axeman’s Carnival. Chidgey’s most recent novel The Remote Sympathy was one of my top novels of 2022 so I couldn’t wait to get my hands on her latest. And I wasn’t disappointed. On the surface, it is a highly entertaining tale of almost magical realism proportions with a talking (and narrating) magpie at its centre. But not far underneath is a dark and sometimes shocking portrayal of economic, social and physical turbulence as greed and misogyny rear their ugly heads. I suppose I should have been forewarned with one of the main characters being an axeman. This book, in my view, well deserves its award as New Zealand novel of the year.

Collected Works by Lydia Sandgren. When I arrived in Stockholm early in 2023, friends were raving about a new Swedish novel by a debut writer – it had just swept Swedish literary awards – and told me that I had to read it. Soon after, an English translation of Collected Works came out and I was able to. I was very pleased that I had this chance. At 700+ pages, it is a saga in the manner of the American novelist Jonathan Franzen. It particularly reminded me of his first novel The Corrections which I loved. Set across several European cities (but mainly Gothenburg in Sweden) over two time periods (1970s/80s + early 2000s), it is largely about relationships – a publisher, an artist and an academic (and their families) work at keeping their lives together as circumstances turn against them. You get deeply involved in their lives and you want to know what happens to them. It is almost like a detective novel as you try to pull the bits and pieces together. But it is also a novel about the creative process as you witness artists and writers both excelling and struggling in their work. This is not an easy read – from time to time the novel gets bogged down with detail – but I highly recommend it. These characters became an important part of my life for three weeks and I missed them badly when I finished reading about them.

The World and All That It Holds by Aleksandar Heman. This epic novel (in scope rather than length) is ostensibly a love story between two male Bosnian soldiers and their child Rahela, and a very fine and merry one it is at first. It is set over a century – from one soldier’s escape from Sarajevo the day that Franz Ferdinand is assassinated, to a week prior to 9/11 with Rahela at a Writers’ Festival in Jerusalem – and it is full of excitement and tension as the intrepid trio flee from Galicia to Tashkent to Shanghai, amidst the Bolshevik Revolution, the Japanese invasion of China and Mao’s Long March across China. In most cases, the trio find themselves on the wrong side of events hence making the extraordinary journey arduous for them to say the least. One is also not sure from time to time whether some episodes are real or not, but this does not stop the novel from being very engaging. It is an epic, beautifully told by a highly skilled writer.

To Battersea Park by Phillip Hensher. To Battersea Park is a lockdown/covid novel. It is not actually about the lockdown or about covid; it is instead a depiction of what it was like to experience both, based largely on the author’s own experiences. Presented as four novellas with four different (but occasionally over-lapping) sets of characters, it depicts the experience of citizens mainly obeying the state’s command to live in isolation within a particular geographical area (near Battersea Park in London in this case) over a particular time period (the first year of the lockdown). As the opening says: “The state gave an order. We obeyed the order. Everyone obeyed the order. And the world changed.” What is clever about this ambitious novel is that its tone ranges from the ordinary and mundane (a family learning how to co-exist under the new circumstances) to the extraordinary (a Stalinist nutter wanting to invade his neighbour’s tranquillity) to the horrific (two lads walking to the sea amidst ominous and apocalyptic surroundings). Collectively, these diverse stories build a vivid and engaging depiction of a time and experience that we can all relate to. A very good – and I suspect important – work of fiction, albeit auto-fiction.

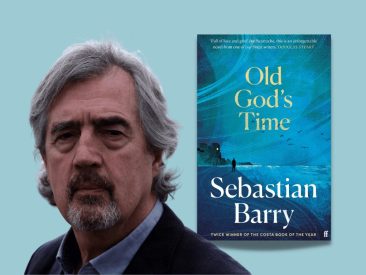

Old God’s Time by Sebastian Barry. It seems so strange to describe this novel as beautiful, but beautiful it is. Beautiful because it is basically a love story – a heart-felt and heart-breaking love between a retired Irish policeman and his deceased wife and family – told in the most exquisite language. Some sentences I had to re-read several times because of their beauty. But why is this situation strange? Because the love expresses itself amidst the most horrible of truths that are all too evident in Irish literature set between the 1960s and the 1990s. Think back to Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These and its links between the personal and the church. Tom, the retired policeman, is trying to live his remaining years in quiet rural surroundings, but well-meaning colleagues from his past unexpectedly bring a cold case to him that opens up memories that have the potential of destroying him. Driven, however, by a strong moral conscience and also immense feelings of self-doubt, Tom feels that he has to co-operate. I loved this heart-wrenching, powerful and beautifully told story. And what a story-teller Sebastian Barry is. He deliberately tried to confuse us from time to time – what is real and what is not real? – but the truth generally shines through. The Guardian reviewer ended his review with, “I don’t expect to read anything as moving for many years.” I think I agree.

In Memoriam by Alice Win. Although set vividly amidst the trenches and battle-fields of World War One – especially in France and Belgium as the terrifying Battle of the Somme takes place – this debut novel is essentially another love story. It depicts two upper-class English school lads (Ellwood and Gaunt) – one a quiet and reticent boxer; the other an aesthete and poet – who search to express their love for each other from the rough and tumble of their public school life to the camaraderie of the trenches to the horrors of the battlefields to the gloom of postwar London. It is in essence a tale of two wars – that of the Great War and that of the love that dares not speak its name. As a piece of writing, the dichotomy between the public war and the private war works beautifully – both are vividly and beautifully portrayed and expressed in this very moving novel.

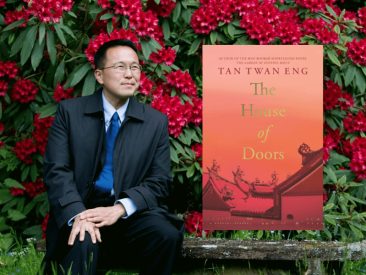

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng. This beautifully written and evocative novel – set largely in Penang and in the early 20th century and featuring three real-life characters/ events (Somerset Maugham and his lover’s visit to an ex-pat family; a shocking murder and subsequent trial of a young ex-pat woman; the Chinese revolutionary’s Sun Yat Sen’s bid to overthrow China’s imperial dynasty) – it is a tale of two halves. One half is personal, featuring both fictional and real-life characters who have largely married or fallen in love with the wrong people. The other half is political featuring a sub-plot of revolutionary fervour and a crumbling empire. Both halves beautifully come together in the titular house of doors. But above all else, this novel is an absolute page-turner and I highly recommend it.

Mister Mister by Guy Gunaratne. I loved Gunaratne’s debut novel In Our Fast and Furious City. I had read no better depiction of the underbelly of a major city (in this case London) since reading Irvine Walsh’s Trainspotting and Gabriel Krauze’s Who They Was. But, as splendidly written as it is, this novel ultimately disappointed me. This was possibly because it featured a topic/subject that didn’t interest me as much as it might others. Yahya Bas, a young Muslim man of Iraqi and British descent, writes (rather than tells) his story of being brought up in London by a group of misfit aunties and uncles (in place of a depressed mother and an absent father), attending various religious and secular schools, becoming radicalised through Britain’s involvement in the Iraq War, joining other radicals in Syria, and eventually repatriating to the United Kingdom where he is ‘forced’ to recall his young life while in long-term detention. Yes, it explores and brings to life through its 186 short sections ‘what makes a radical’ in today’s United Kingdom – set amidst shadows of recent terrorist bombings and murders – but I could not connect with the main character as he was drawn. Others might be able to.

August Blue by Deborah Levy. This novel, which swings between realism and surrealism and between darkness and humour, is primarily about memory loss and resurrection. Elsa, a world-famous concert pianist, loses her memory to devastating effect when she is performing in Vienna. In addition, she holds very little recall of her ancestry and decides that she has to re-connect with whatever family she can locate. She attempts to do this by setting up various liaisons and interactions with friends, lovers, occasional clients and (most importantly) her dying foster father and his partner. The interactions between her and her foster father especially lead to the drama of the piece. But a knowledge of the concert pieces played by Elsa in the past, especially Rachmaninov’s First Symphony, might have helped me to understand the metaphors that appear to underpin the novel. Ultimately, it did not touch me as it has touched others.

THEATRE

Toward the end of our stay in Europe, I returned to London for a long weekend (Coronation weekend!!) and fitted in 3 plays over this period, two of which were new and one was a revival:

A Little Life by Ivo Van Hove, Koen Tachelet and Hanya Yanagihara. The novel that this play is based on is one of my favourite novels of the past decade. So I was incredibly excited to learn that the author of the novel (Yanagihara) and one of Europe’s most innovative theatre directors (Van Hove) had collaborated on a dramatization of the novel. The result is incredible. The four-hour production is powerful and terrifying; almost as powerful and terrifying as I remember the novel being when I read it in 2015. I say ‘almost’ because I was occasionally able to anticipate key moments having read the book. But this didn’t distract. Its focus is on Jude (a successful and charismatic young New York lawyer who has been severely abused as a youngster and is consequently addicted to self-harming) and his beautiful interactions with his three most loyal buddies. It is graphic, yes; but not gratuitously so. The staging along with the acting is amazing (James Norton is incredible as Jude) with the production fully deserving its standing and very loud ovation at the end.

The Motive and the Cue by Jack Thorne. Being about the famous 1964 Broadway production of Hamlet, directed by Sir John Gielgud and starring Richard Burton (with Elizabeth Taylor ‘hanging around’ in the background), I suspected that this new play would be fabulous. Burton and Taylor were at the height of their fame; Gielgud’s star was not shining as brightly as it once had; and the artistic tensions between the modern and the traditional seemed inevitable as two opposing giants of the theatre were set to fight over interpretation. And fight they did – Burton overtly; Gielgud more subtly. This made for an enormously entertaining night in the theatre with performances that blew me away, especially Mark Gattis as Gielgud. I could’ve sworn that the old knight of the theatre was actually on stage.

Dancing at Lunghnasa by Brian Friels. Knowing this classic (a tragi-comedy about four Irish sisters living in near-poverty in the 1950s) well and having loved it in the 1990s when I first saw it at Downstage Theatre in Wellington, I was so excited about seeing a new production, especially at the National Theatre and on a vast stage. But maybe it required a more intimate production than the National could give it, because the emotions that swept through me in the 1990s just didn’t touch me this time around. I wondered if the play had become dated; I wondered whether I’d become more cynical. But I think it was the production itself – much of its power relies on a young actor (playing the illegitimate son of one of the sisters) narrating the story of his ma and his three aunts, but the young actor this time around didn’t engage or move like I remember being moved. This was disappointing.

Upon returning to New Zealand, I have also seen a production of Prima Facie (by Suzie Miller) at Circa Theatre in Wellington. This is an outstanding play and the production I saw (directed by Lyndee-Jane Rutherford) was also outstanding. I could not get into the Auckland production as it was booked out so feel pleased and privileged to have seen the Wellington production. If you get a chance to see this play anywhere, take the chance. It is a solo show (brilliantly performed by Mel Dodge in Wellington) featuring a ruthless prosecuting lawyer having the tables turned on her when she decides to lay charges against a male colleague who she believes has raped her. It is heart-breaking. I have heard talk that the production (with its simple but very effective staging) will tour. I hope it does as it deserves to be widely seen and experienced, especially by those involved in the legal system.

| Much more in a few months as I will have finished reading the short-listed (and many of the long-listed) contenders for the 2023 Booker Prize for literature, and I will have finished viewing what looks like an exciting line-up for the NZ International Film Festival. |

What do you think? Share your thoughts...