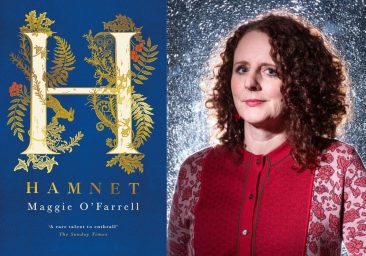

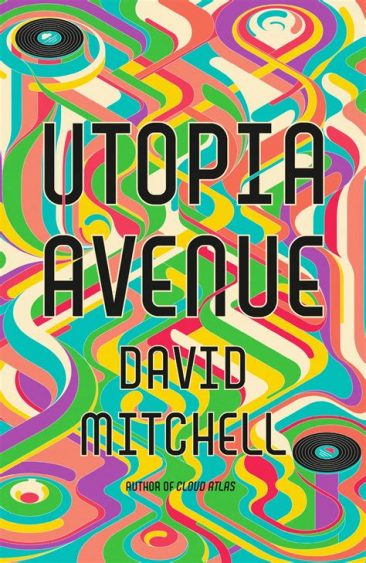

At the end of my last Arts Update (August 2020), I was part way through reading Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet and about to start David Mitchell’s Utopia Avenue. I would highly recommend both of these novels, but especially Hamnet.

Set in seventeenth-century Warwickshire (England), Hamnet is a beautifully written fictionalisation of the ups and downs of William Shakespeare’s family and particularly the tragic death of his son. Having caught and died from the black plague, its connections with today’s pandemic world are incredibly powerful. I shed many tears while reading the second half of the book, and it evoked seventeen-century England (particularly from a domestic perspective) far more vividly for me than did Hillary Mantell’s widely acclaimed The Mirror and the Light.

David Mitchell’s latest, Utopia Avenue, also lived up to my expectations. Set in the London music scene of the 1960s and populated by personalities such as Mick Jagger, David Bowie and Eric Clapton, it is a reasonably straightforward and very engaging narrative of one (fictional) band’s rise to stardom and their fortunes thereafter. Although more akin to the gritty realism of Mitchell’s previous novel Black Swan Green (set in the same time period), it contains elements of the magical realism prevalent in his acclaimed books Cloud Atlas and The Bone Clocks.

Booker Prize Shortlist

No sooner had I completed the above books but the Booker Prize longlist and subsequent shortlist was announced. I consequently set about reading all novels on the shortlist (I had read one previously; Maaza Mengiste’s The Shadow King) so as to make up my own mind about ‘what should win’. In order of reading:

Real Life by Brandon Taylor. This novel involving a young black gay doctoral student facing personal and academic challenges did not fully engage me. Taylor’s strong authorial voice often got in the way for me, meaning that I could not fully connect with the campus world that Taylor had created.

Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi. Although totally different in setting and characterisation (tensions between generations in contemporary India), I felt the same about this novel. Its poetic tone largely alienated me from the sense of jealousy, cruelty, obsession and betrayal that I felt the author was trying to depict.

This Mournable Body by Tsitsi Dangarembga. This novel, set within the crumbling infrastructure of Robert Mugabe’s Harare, enthralled me. I felt that I was experiencing the downward journey that Mugabe’s Zimbabwe had experienced as I read about the main character’s downward spiral from hope to despair. At this stage in my reading, I predicted that this beautifully written novel would deservedly win the Booker Prize.

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook. This lengthy novel, inspired by the world’s climate crisis, engaged me from time to time. Apocalyptic in tone, it tells the story of a family escaping from a decaying American city and trekking across a state-controlled and dangerous wilderness. However, I found myself losing engagement when the author moved away from the narrative to explore diversionary asides, as interesting as some of them were.

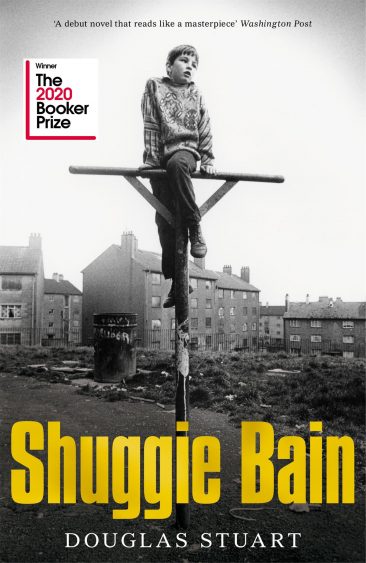

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart. I suggest that this novel is a masterpiece and will become the 21st century’s Catcher in the Rye. The story of a young Glaswegian boy’s relationship with his alcoholic mother and siblings during the Thatcher years had me enthralled from cover to cover. Although depressing on the surface, a sense of warmth and vibrancy is just one level below the depressing surface. I could not put this novel down.

| I was delighted when Shuggie Bain was declared the winner. I would also nominate it as my novel of 2020 but followed closely by Hamnet (by Maggie O’Farrell) and Rainbow Milk (Paul Mendez). These are the books that I bought for my friends for Xmas. I also recommended that they read Hurricane Season (by Fernanda Melchor) if they wanted to be challenged by true grit in today’s tough world.

|

National Book Award

The American equivalent of the Booker Prize is the National Book Award and the shortlist for this was announced soon after I finished reading the Booker Prize nominees. Consisting of four novels, I was delighted that Shuggie Bain was one of the four. The others (in order of me reading them) were:

Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu. This novel, written in the form of a television script, is an amusing exploration of Asian stereotypes (and ultimately racism) in the American film world. The protagonist’s main role is generally to be Generic Asian Man at the back of a scene; his goal is to become Kung Fu Guy. I enjoyed the ideas in this novel but wasn’t always engaged in the plot.

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Aman. I really enjoyed reading this novel though found it quite apocalyptic and chilling in parts, especially in the current context of America’s political and social turmoil. It is a strong narrative about a white middle-class family enjoying a summer vacation and having to suddenly share their accommodation with an elderly black couple because the ‘end of the world’ appears to be looming around them. Or does it?

A Children’s Bible by Lydia Millet. This is another ‘possible end of the world’ novel set within the current context of America’s political and social turmoil. It is arguably more chilling than Leave the World Behind in that children are to the fore this time. Despite this, I enjoyed this novel very much as an exploration of the generational divide and what could be at the end of ‘the revolution’. A Lord of the Flies of the 21st century?

| Shuggie Bain followed by A Children’s Bible and Leave the World Behind would have been my choices for the National Book Award. But the judges saw fit to award it to Interior Chinatown which they described as ‘wrenching, hilarious, sharp, surreal and above all, original’. I would not have used these descriptors.

|

Other Books

I have read eight other books over the Xmas holiday period, including the latest from some of my favourite novelists:

Trio by William Boyd. I suggest that there is no more engaging story-teller writing in the UK today than William Boyd. I have been reading Boyd prolifically since the early 1980s and I have never been disappointed. Trio, his latest novel, lives up to my high expectations for this writer of tightly plotted narratives. A combination of intrigue, romance and adventure, it is set in 1968 (the year of student riots across the world) and amongst film-makers, writers and actors (all attempting to ‘find themselves’) as they indulge in the creation of an experimental movie. For me, a real page-turner and a book that many of my friends are now reading.

A Small Revolution in Germany by Phillip Hensher. This novel was not a page-turner but its plot of a young politico’s growing up set across two time-spans (1970s and 2010s) and two countries (UK and Germany) interested me enough to keep reading. I am a huge fan of Hensher (particularly King of the Badgers, The Emperor Waltz and The Friendly Ones) but this novel did not engage me as much as the others.

Mr Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe. Having loved Coe’s last novel (Middle England), I was so looking forward to reading Mr Wilder and Me. I was not disappointed. To me, it didn’t have the depth of Middle England (which was a fictional look at the impact of the Brexit vote on the UK), but this coming-of-age story (set largely in the 1970s) and intimate portrait of a real Hollywood director (Billy Wilder; director of Double Indemnity and Some Like It Hot) engaged me to the end and is also being read widely by my friends.

Islands of Mercy by Rose Tremain. This novel reminded me greatly of one of my favourites from 2019 (The Essex Serpent by Sarah Perry). Set in the 19th century between Bath and Borneo and amongst a range of fascinating characters, it contains sufficient degrees of adventure, science, romance and social comment to both challenge and engage me. To me, it was on a par with my two favourite Tremains: Sacred Country and The Road Home.

Shelter in Place by David Leavitt. One of my friends nominated this novel as ‘the worst of 2020’. Although I would not nominate it as ‘the best’, its satirical look at the antics of a group of New York liberals responding to the election of Trump (it opens with one character asking another, “Would you be willing to ask Siri how to assassinate Trump?”) amused and engaged me. My friend hated the selfish and self-obsessed characters; they made me laugh.

Snow by John Banville. I did not know that the esteemed Irish writer John Banville wrote who-dunnits in the style of Agatha Christie, but this is what this book (set in the 1950s at a grand Anglo-Irish manor and involving the murder of a local priest) most certainly is. Unlike Agatha Christie though, it also contains some fascinating social commentary, pertinent to the time and location of the novel. I have to admit though that I correctly predicted its outcome before reading its final page. But I would still recommend it as a great yarn and a page-turner.

Lucky’s by Andrew Pippos. I read a rave review of this first novel by Australian-Greek writer Andrew Pippos in The Guardian (one of my main sources for new books) and I loved it. It’s an inter-generational story generated by a Greek immigrant who establishes a chain of ‘greasy spoon’ restaurants across Australia in the 1950s and it is another page-turner as one discovers what happens to these restaurants and the people who run them. It’s also a mystery as its key characters discover what had ‘really happened’ to their ancestors and why they are the people that they are now. In tone, it reminded me of the best of Peter Carey’s Australian-based novels.

Finally, some non-fiction. Another of my favourite books from 2019 was The Spy and the Traitor by Ben Macintyre. I love spy stories – fiction and non-fiction – so I was very excited when I read that Macintyre had just published Agent Sonya, a tale of a Mrs Burton who seems to epitomise rural British domesticity during World War II but who is in fact a colonel in Russia’s Red Army and a highly trained spy. This book enthralled me – Macintyre is a great story-teller – almost as much as The Spy and the Traitor did.

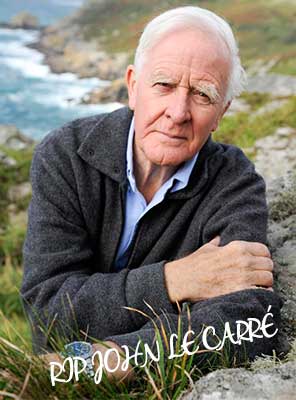

On a sadder note, I was very saddened to hear of the passing of the great spy writer John Le Carre in December. I have been reading Le Carre since I was at secondary school (The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was my introduction to him) and always remember the eminent New Zealand novelist Maurice Shadbolt (who was the subject of my MA thesis in the 1980s) nominating Le Carre as ‘the greatest living novelist’ in a conversation with me.

I’m currently three-quarters of the way through Martin Amis’ Inside Story: How to Write which the author describes as a novel but also as ‘auto fiction’ – a deliberate cross between autobiography and fiction. I find it fascinating – any book that explores the writing process both in fictional and real terms and that incorporates personalities such as Saul Bellow, DH Lawrence and Philip Larkin in its telling of the tale would fascinate me – though I concede that many others might find it confusing and convoluted.

What do you think? Share your thoughts...